In September 1980, I joined the CMA

Consulting Group, a consulting firm dealing in construction surety problems and

special projects and investigations.

Shortly after joining CMA,

I was added to a team organized by the company to help Nigeria solve a

number of problems.

Nigeria is a West African nation located on the coast off the

Gulf of Guinea, surrounded by the neighboring

countries of Benin,

Niger,

Chad

and Cameroon. Many years prior to my association with CMA, Nigeria had a very prosperous

agrarian economy that enabled them to export large quantities of surplus food

and use the income for internal civic improvements. The economy was totally dependent upon local

tribes providing workers to plant and harvest a variety of foodstuffs,

including yams, grain and nuts plus non-edibles, such as cotton, rubber and

minerals. When oil was discovered, the

natives deserted the farms and mines to work in the new oil fields at a

substantial increase in personal income.

The abandoned farms went fallow and the food surplus that Nigeria had

enjoyed and that had provided the nation with an export income, vanished. In no time at all, Nigeria went from a food-exporting

nation to a food-importer. The increased

income that had attracted the natives to the oil field jobs vanished as well

since they were forced to spend more for the increased cost of imported food. It wasn’t long before Nigeria was

faced with a serious problem: the nation was receiving large sums for the newly

discovered oil, but because of the changes to their economy, they were spending

more on imports. In addition, corruption

was draining much of the oil income.

Fortunately, there were

knowledgeable people in and out of the Nigerian government who recognized that

relief was needed to avoid the possibility of a future famine. Concurrently, the political situation existing

in Nigeria

at that time discouraged foreign nations from rushing to Nigeria’s

aid. To ease the international problem, Nigeria decided

to seek options for the short term that would provide immediate assistance and

alleviate the long-term problems. Before

my joining CMA, a negotiation had

been conducted with Nigeria

and CMA

had entered into a contract to prepare a feasible study on developing these

options. CMA

sent a team to Lagos

to conduct a field investigation while fleshing out the home team with new

hires. I was part of the latter.

Prior to my joining CMA, our field team reported that piracy was

rampant in the Gulf

of Guinea. While the nation had ports at Port Harcourt and Lagos, they were

inadequate to handle the increased volume of shipping needed by the oil

companies to support the oil fields and by the government and private firms to

receive normal imports. Ships would

arrive and be forced to anchor in the Gulf of Guinea

for weeks while waiting their turn to dock.

In the meantime, the radically changed economy was forcing an

increasingly frustrated native labor force to supplement their income to

survive. The large number of

unprotected, anchored vessels provided a possible answer. Many natives decided to band together in

illegal clandestine activities in the gulf.

Operating at night, using speedboats to reach and board the anchored

vessels, the part-time pirates would remove selected items from the vessels for

later sale on the lucrative black market that had sprung up along the coast. There were even reports of pirated oil

equipment being sold directly to original owner oil companies.

Enraged at the substantial

losses to pirates, the initial reaction of the government was to provide a

defense force to counter the pirates and defend the cargo vessels against these

raids. When it was realized that there

was a strong possibility that corrupt government officials, police and members

of the Nigerian armed forces were actively participating in the piracy, a

decision was made not to resist and to permit the pirates to take whatever they

wanted. The supporters of this decision

noted that casualties were only experienced when the ship’s crew resisted. While undoubtedly saving lives, the decision

to permit the continued theft raised maritime insurance rates, which increased

the costs of imported goods and further aggravated the failing economy. The government piracy decision, however,

permitted CMA to divert our field

team to solving their original task, that of solving the new options problem. Our efforts were now concentrated on the

preparation of the feasibility study.

It was the goal of the

Nigerian government to eliminate, or substantially reduce, imported food from

the diet of their citizens. To

accomplish this goal, the offered food had to be normal to the average

Nigerian’s simple diet, be plentiful and

readily available, and it had to be priced at acceptable cost. In turn, increased domestic food production

required more workers than were currently available because of the higher pay

of the oil fields. That meant finding a

means of luring workers from their lucrative oil field jobs. It

became a problem of how to increase the worker’s pay or reduce his cost of

living – or a combination of both. While

increasing the workers pay could solve the problem, if the workers were attracted

to the offer at all, it was an exercise in futility because the oil companies

had unlimited funds and could counter the government’s offer and easily recover

the additional costs in subsequent sales in a seller’s market. What to do?

The CMA home office had many

meetings on this point. I don’t recall

who solved the problem (I think it was the woman whom I was paired with on the

team), but the final decision was not in trying to out spend the oil

companies. She proposed that we offer

the workers ‘a piece of the action,’ by offering to make them a part of the

team and share in the profits for as long as they remained in the program.

The study that was developed

proposed an agricultural plan consisting of 3-5 small farms with one central

equipment facility serving the farms, all located adjacent to an existing

road. Each farm would include a one-room

dwelling to house the farmer and his family.

The building could be poured concrete cast on site or a prefabricated

structure erected on site. Neither would

be less attractive than existing homes used by the native workers. One big advantage with the offered family

home was that workers currently employed at the oil fields rarely, if ever, had

their families with them.

The central equipment center

would include all equipment deemed necessary for the operation of the

farms. While each farm would have its own

supply of hand tools, the center would have larger items, such as trucks,

tractors and any required special farm equipment. The center would also be used to make

repairs, store fuel and supplies and, in general, do all the tasks necessary to

support the farmers and their farms. Because

of the added skills required to operate the center, the compensation would be

greater.

Simply stated, in operation

the farmers would raise crops on their farms supported by the center. Some harvested crops would be moved to a

roadside food stand for sale to the general public. The government would purchase surplus food at

every harvest for distribution to the poor and for export sale. .

A European Agronomist would

run the first farm complex with a small staff under contract. His task would be to train the farmers and

the equipment staff. The trainees would

run follow on farm complexes.

The farmers and the natives

operating the equipment center would be paid a wage plus a percentage of the

profits of the complex and be provided with living quarters for them and their

families. If the farmer remained with

the complex for a predetermined number of years, the land, building and tools

would become his property. If the

operators of the equipment center remained with the center for a predetermined

number of years (not necessarily the same number of years as the farmers, probably

more), their quarters plus a percentage of the value of the equipment would be

titled to them. In both instances, no

specific time period was noted because the affected factors would not be known

until the plan was finalized. At the

time, the thinking was three years for the farmer and five years for the

operators. After three years, the farm

complex would become a worker-run co-operative.

Transferring title to a one-room concrete home may not appear to be very

attractive, but in a country where most tribal native quarters were a fragile

hut made from branches and mud, the offer had merit.

The initial program was not

expected to show a profit because of the high start up costs and its planned use

as a training center, but in the follow on complexes, with the Agronomist no

longer needed, with equipment on site and with training completed, the realized

income from sales would begin to shift to the bottom line.

It did no good to raise food

for the locals if there were no means of getting the food to the

consumers. The southern half of the

country was divided into a number of approximately equal parts, each part

having at least one road for access, thus, placing the food stands adjacent to

roads permitted the locals easy access to the food. Food for export would be trucked to an

embarkation point.

With adequate investment seed

money and native farmers, a new farm complex could be started every year or

so. Ultimately, the southern half of the

country would have many farm complexes, owned and operated by the workers. Adequate food supplies would be raised for

domestic consumption and eventually enough to reinstate the old agrarian export

program destroyed by the discovery of oil, but problems remained. The less hospitable Nigerian Islamic north

country wasn’t included because of the nature of the land, which was mainly

forested. The government didn’t have a

valid plan for resolving the existing political and ethnic problems that

prevented expansion into the north. Ways

to raise the seed money necessary to get any version of the study started

continued to evade them. The oil money was mostly gone, having been lost to

rampant corruption or having been used to fund commitments more politically

correct. European and American

investors, who had shown an early interest in the program through the OKPI

Development Company, were now reluctant to take part. Without investment money, another source of

funds was desperately needed. In my

discussions with the U.S. State and Agricultural Departments, the message was

clear: Nigeria

was a high-risk business environment that required too many safeguards. They strongly recommended no investment to

any who would ask.

Someone in the Nigerian

government suggested harvesting their plentiful forests. This constituted an entirely new project with

new objectives and proposals. Some

suggested substituting the proposed forest program for the farms. Since the purpose of the farms program was

employment for former farmers and the restoration of food exports, the proposed

substitution was rejected and a preliminary review of the forest program

conducted.

The majority of the forests

under consideration for harvesting were in the hostile north. Would the northern locals agree to the

cutting of “their” timber? If so,

wouldn’t they expect compensation in jobs, a share of the profits, or both? It would only seem fair that timber cut in

the north would employ locals. But there

was a more pressing problem. There were

few, if any, trucks available to haul timber and few adequate roads in the

north for the trucks to haul on. During

the review, it became apparent that the cost of the proposed timber program

would easily exceed the cost of the farms program. The sale of the timber would generate a

profit, of course, but funds would first be needed to build roads capable of

handling the anticipated very heavy traffic that the timber harvest would

create. Large trucks would have to be

purchased and drivers would have to be hired and trained. No one in the government appeared

knowledgeable on the availability of the tools needed to do the work and the

assumption had to be made that procurement of tools for cutting timber would

add a substantial sum to the costs. The

problems were growing like Topsy. I

couldn’t help but remember the words of a poem on how a battle was lost because

a nail was lost. Truly, this was the

case in Nigeria.

Though the farm plan was

self-supporting, without seed money and because of unsettled conditions in the

country, foreign investors were not interested in what they considered a very

risky investment – a position supported by the U.S. State and Agricultural

Departments. The government was financially

incapable of initiating the programs without outside assistance and was forced

to place both programs on hold while efforts were made to find a solution to

what appeared to be unsolvable problems.

The oil money was the logical answer to the problems, but that required

an end to existing corruption, something that was not about to happen.

Though the farm plan was

self-supporting, without seed money and because of unsettled conditions in the

country, foreign investors were not interested in what they considered a very

risky investment – a position supported by the U.S. State and Agricultural

Departments. The government was financially

incapable of initiating the programs without outside assistance and was forced

to place both programs on hold while efforts were made to find a solution to

what appeared to be unsolvable problems.

The oil money was the logical answer to the problems, but that required

an end to existing corruption, something that was not about to happen.

What I have described is one

particular business problem that CMA

faced and ultimately abandoned. But

there were other difficulties that all businessmen doing business in Nigeria faced

on a daily basis. Transportation using a

taxi or rented car was impossible. The

only certain means of getting around a city such as Lagos was to locate a local native who owned

a vehicle and hire him for 24-hour transportation service during your entire

visit. In operation, he lived in his car

and was always available to move you around the city to wherever you wanted to

visit, day or night. Of course, in a

country with the climate of Nigeria,

this raised several hygiene problems, which you couldn’t help but notice but

had to ignore if you ever wanted to get around the city. Telephone service was spotty at best. There were many days when telephone service

didn’t exist. The wise businessman hired

a 24-hour messenger to guarantee delivery of his messages. Most of these messengers lived in the car

with the driver. Normally, the hired

driver would recommend one of his friends for the messenger tasks.

Sanitation in Lagos was not always the

best. There were days when heavy rains

created local flooding and caused the sewers to overflow into the streets creating

odorous trips – another good reason to have your own driver who was familiar

with flooding problems. On such days,

walking in Lagos

could be very unhealthy. I remember a

conversation that I had with one of our field managers on his return visit from

Africa.

He described a day when one of the main streets in Lagos was flooded from heavy rains and sewage. His driver was taking him to a meeting at a

hotel or office building. His

description of his visit could have been the subject of a comedy written for

the movies. He said the car passed

through the streets on his way to his destination creating waves that imperiled

pedestrians. When he arrived, he removed

his shoes and socks and placed them in his suit pockets, rolled up his trousers

to mid-calf, and stepped into the filth and waded to the building where a

doorman was waiting for him. The doorman

had a garden hose which he used to flush his feet with what he hoped was clean

water, offered him a towel and a folding chair for him to dry his feet and

replace his shoes and socks. The most

humorous part of this entire event was that both the visitors and the doorman

went through the entire process without batting an eye. Everyone accepted what was happening as

normal.

And this was just one

assignment during my tour at CMA. Even business has its funny moments.

Schedule of Photographs

1. Map of Nigeria.

2. Broad

Street, Lagos.

3. Typical

street.

4. River boatman

5 Sketch of planned farm complex

6 Nigerian Architecture

7 Not too friendly native in an outlying village.

8 Local river boatman.

9 River boating delivering food.

10 Women dancers at a wedding.

11 Shops near Efferun.

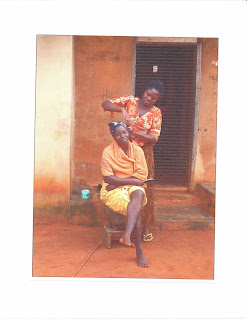

12 Outdoor beauty parlor

September 2007

LFC

No comments:

Post a Comment